Using Self-Collected Data to explore The Impact of Endurance Training on my Cholesterol

As you may already know, I often use "self-tracking" to learn new things about myself. If you are not familiar with what this entails, self-tracking (in the context of health and wellness) can be defined as a social movement in which individuals collect data about their own health, sometimes using tools equivalent to those of professional labs.

These individuals often have no formal training in medicine, research methods or statistics (like me!). However, they all believe in empowering people to take control of their health.

From helping prevent disease, to personalizing our diet and optimizing the way we train or rest, the possibilities are endless.

The rise of sensors, direct-to-consumer tests and health tracking software tools, makes it possible for anyone to quantify different aspects of their lives.

I. What I did

I am usually not a big fan of endurance activities (see my self-tracking experiment "Training for strength or endurance"). However, I decided to run the NYC marathon, mostly because this was the last year I was able to defer without losing my (hardly-earned) entry :)

I've also heard many times that the race itself was very beautiful, since you get to see the streets of New York and how they change from one borough to another, not to mention the breathtaking views from a few NYC bridges that you cross as part of the race. (And all this was true!)

I trained for the race mostly between end of August 2017 and early November 2017, and I used this opportunity to try to explore the impact of this new type of physical activity.

I also gradually reduced my "regular training," which consists of a mix of power and power endurance (usually never more than 60-75 minutes). By end of September, I was already running all the time.

II. How I did it

1. I used NYRR Virtual Trainer by Runtrix to design a program

NYRR Virtual Runner is a software that helps you build dynamic training plans. It was recommended by NYRR (New York Road Runners), the organizer of the NYC Marathon.

The tool customizes your plan based on your running history (which was convenient since I've already done a lot of runs with NYRR over the past few years, even though none of them was longer than a half marathon. As a result, all they had to do was upload all my race history when I signed up).

The plan is dynamic; it can change anytime based on your performance. I chose the the 16-week "conservative" plan, but I also modified it based on other factors, such as work load, travel, how I felt, and (of course) the other data I was collecting (see below)!

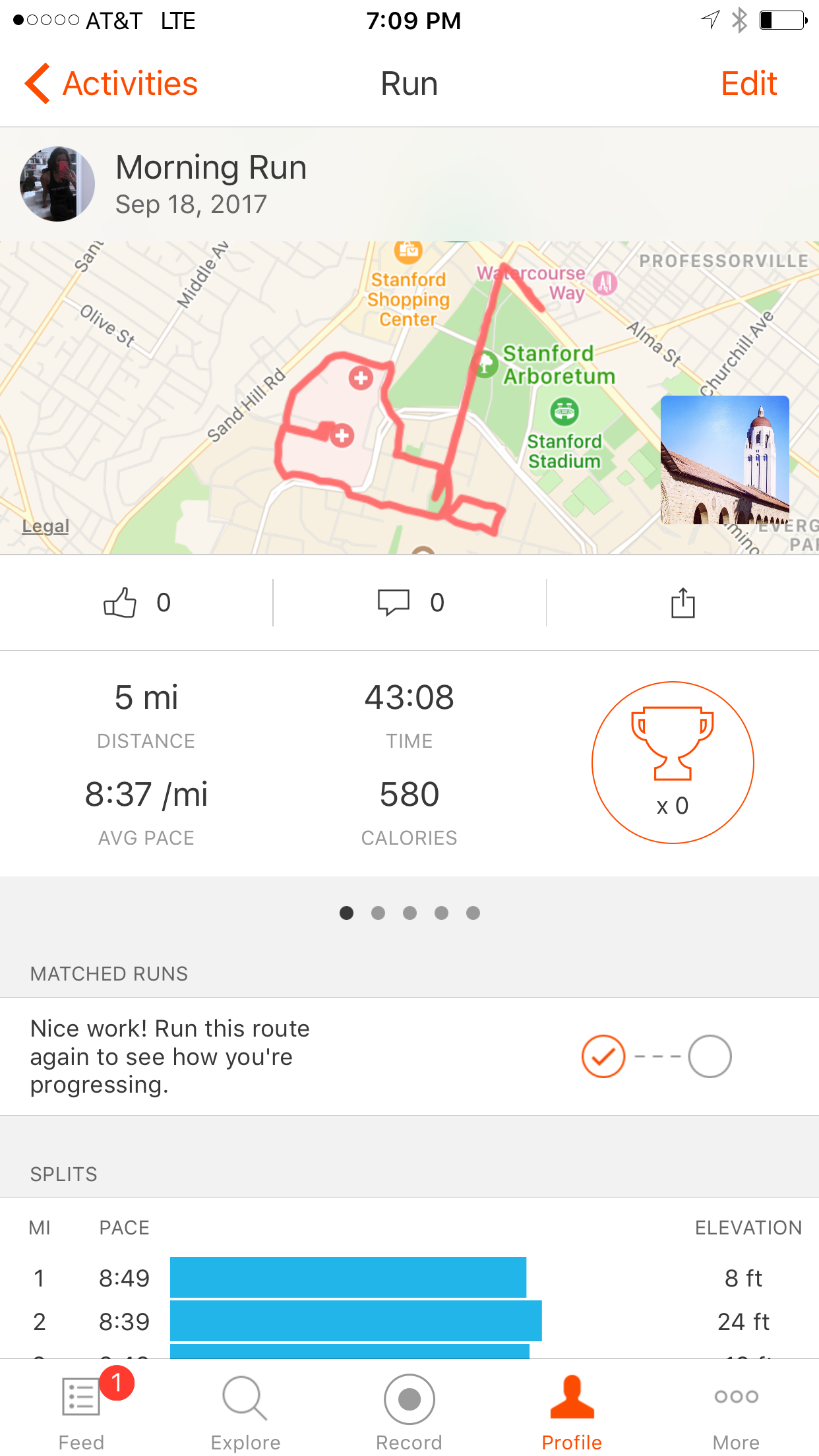

2. I used my Strava account to track performance

I don't use Strava that much in general, since it's mostly for running, cycling and swimming. However, I use it by default every time I am not running on a treadmill.

As Strava addicts would say, "If it's not on Strava, it didn't happen." :-)

It's obviously great for tracking and analyzing runs. The interface is beautiful too!

In this case, I used it to keep track of my average pace. As I will explain later, this is relevant for measuring "intensity."

I used this device to track my glucose level. All I had to do was wear a sensor on my arm. If I want to get a reading at any specific time, I just scan the sensor.

The readings show the current glucose level, but the device can store data continuously. It also lets you download / export the data anytime.

I used the device mostly to manage my fueling strategy, especially for the long runs. Since I was new to distance running, this was very eye-opening.

In the past, I used to run half-marathons without worrying much about my food intake. I used to only eat before and much later after the run.

So my first intuition was to run and not really worry much about food intake...until I started using my CGM device. I realized that I was running with (very) low glucose levels (see photo) most of the time.

This forced me to increase my carb intake (and reduce fat and protein intake). See below what this did to my cholesterol!

4. I used the CardioChek® Plus Analyzer to test my blood lipids

I used this whole blood analyzer to measure lipids (Cholesterol, HDL and triglycerides).

Unlike my CGM device, this tool required me to take blood samples each time.

Most importantly, I did this as part of a participatory, high-frequency blood testing project.

A few months ago, a group of 21 Quantified Self enthusiasts (including myself) started a new collaborative project called “Blood Testers.”

Our immediate goal with this experience was to learn more about ourselves through high-frequency self-testing of blood lipids (i.e., cholesterol and triglycerides). Our long-term goal was to help advance self-directed research by better understanding what makes these types of collaborative self-tracking projects succeed or fail.

In my case, I wanted to explore the impact of endurance training on my cholesterol. More precisely, I decided to look at two components: the long-term and the short-term impact of endurance training on cholesterol.

4.1. Understanding the "long-term" effect of endurance training on cholesterol

Note: "Long-term" is defined here as two months. The goal in this section is to see how my cholesterol changed between the beginning and the end of the training period.

It is obvious and widely accepted that exercise helps improve cholesterol. However, I was surprised to learn that, as of today, there is very little consensus about the impact of exercise intensity, duration, frequency, type and mode on cholesterol.

Is it better to engage in moderate activity? Would strength training help improve your cholesterol better than cardio, or better than cardio and strength combined? What is the impact of distance running on cholesterol? Is it more about mileage (number of miles covered per week) or intensity (percentage of maximum heart rate, HRmax)?

Researching the scientific literature on exercise and cholesterol quickly became confusing (since there is very little consensus on the subject), so I decided to narrow down my research to running and cholesterol. I found that studies often looked at two variables when it comes to running and cholesterol: mileage and intensity.

As part of this experiment, I had to increase my mileage every week, until I reach the point where I can safely complete a 26 mile race. As a result, it was interesting to look at the impact of mileage on my cholesterol.

If we define intensity by percentage of HRmax, then the assumption here is that my intensity remained somewhat low, since I usually had to run at my marathon pace (i.e. a low, "boring" pace), even when I was covering much shorter distances. The only exception would be speedwork sessions, but I didn't do much of it anyway.

Here's what is supposed to happen, according to the research:

4.1.1. Impact of mileage:

This study demonstrates that, for men, HDL-cholesterol (i.e. the "good" one) increases with higher running mileage, and decreases within days of stopping exercise when caloric and alcohol intake remain elevated (1). In fact, most of the exercise training studies identify a weekly mileage threshold of 7 to 10 miles/week for significant increases in HDL-C in men (2).

In women, the volume of exercise seems to be more important than the intensity of exercise for influencing HDL-C levels. Most studies suggest a large volume of exercise is necessary for significant HDL-C changes in women, however, the exercise volume threshold has not yet been defined (2).

4.1.2. Impact of intensity:

Exercise intensity studies on men show that men increase their HDL (i.e. "good" cholesterol) by increasing exercise intensity to 75% HRmax or above (2).

Unfortunately, training studies attempting to assess the role of exercise intensity on HDL-C in women are few and report conflicting results. Most of the research suggests that women (pre and postmenopausal) with low levels of HDL-C are more likely to respond positively to exercise training. Duncan et al. (1991) reported similar increases in HDL-C levels in women (29-40 years) following 24 weeks of walking (4.8 km/session), regardless of intensity. This finding suggests that moderate exercise will raise HDL-C levels as much as intense exercise. In addition, Spate-Douglas and Keyser (1999) reported that moderate-intensity training over a 12-week period was sufficient to improve the HDL-C profile, and high-intensity training appeared to be of no further advantage as long as training volume (total walking distance per week) was constant. Conversely, Santiago and others (1995 ) reported no changes in HDL-C levels in women following 40 weeks of endurance training similar to the program in Duncan’s study. However, the women in Santiago’s study had higher initial HDL-C levels than the women in Duncan’s study (65 vs. 55 mg/dl). These findings also support that women with lower levels of HDL-C are more likely to see increases in HDL-C with exercise training (2).

Last but not least, I didn't find much on distance running and triglycerides. (let me know if I missed anything?)

This is unfortunate, because that's where my results were the most surprising (!)

4.2. Understanding the immediate effect of endurance training on cholesterol

In the previous section, I looked at how my cholesterol changed throughout the entire September-November period.

This section focuses on how my cholesterol, HDL and triglycerides levels changed on a moderate activity day, as well as on a "long run" day (in addition to rest days).

Here's what I did: On the days when I was running, I took a "before" and a "right after" measurement. Moreover, I tried to measure fasting cholesterol on most days.

(The process was somewhat cumbersome, since I had to take a blood sample each time, so unfortunately I didn't do it every single day. However, there were days when I took 4-6 measurements).

5. I tried food logging (again)

I also tried to keep a manual food log, but I have to say that I wasn't very good with that.

I did, however, calculate my caloric intake (in my head) with the goal of keeping it somewhat consistent with the amount of training I was doing. This is what I usually do...

I managed to do it to a certain extent. This was especially tricky because I had to move to 60% carbs towards the end of my training to be able to cover the distances required without being constantly in the low (red) blood glucose zones.

The tricky part here is that it's very easy to get to 1700-1800 calories per day or more (while still being under the impression that you're barely at 1000 calories), if you start eating a lot of pasta consistently for the first time (!)

Overall, my body weight didn't change much. However, I did gain body fat (and lose muscle).

III. What I Learned

Things to keep in mind:

Note (1): During the couple of weeks preceding and following my marathon training, I was mostly resting and/or recovering (i.e. I was not doing anything strenuous).

I went back to my "regular training" towards mid-December. This consists of high-intensity power and power endurance activity for 60-75 minutes about five times a week, as well as cardio once a week and one rest day. This part is colored in gray in the chart above.

Note (2): The CardioChek® Plus Analyzer calculates LDL (LDL = Total cholesterol - HDL -.25*Triglycerides). This could make LDL results less accurate than the rest.

Insight #1

My total cholesterol went down as I increased my mileage, reaching all-time lows of 124 mg/dL right after my 20 miles prep race and 120 mg/dL after completing the marathon.

My fasting measurements also decreased to about 135 mg/dL around race day, down from about 160 mg/dL at the beginning of the training.

It's important to keep in mind that when I took my post-race cholesterol measurements, my blood glucose level was always in the normal range (including during the full marathon!). I was only able to do this because I was using the continuous glucose monitor; my intuition would have been to not eat, especially that didn't feel like I needed to (at all), and I really dislike running gels :)

In other words, my cholesterol was at these levels despite the fact that I was consistently in the normal range for blood glucose.

Insight #2

My total fasting cholesterol remained low a couple of weeks after the race, despite the fact that I was not training and was maintaining a relatively high daily calorie intake. However, it did end up increasing a lot later in November (the race was on November 5, 2017) to about the same level as it was before I started marathon training (!)

Insight #3

After I went back to my "regular training" towards mid-December (as described above), my total fasting cholesterol went down again in February 2018 to about the same level as it was on race day!

This could mean that exercise intensity also decreases my cholesterol, just as much as, if not actually more than, duration/mileage.

Insight #4

Both my HDL and triglycerides / LDL decreased as I increased mileage. The surprising part here is that my HDL levels decreased as well.

However, this was only the case until about the first week of October (four weeks before the race). See below.

Insight #5

My triglycerides and LDL started to increase significantly about four weeks prior to the race. I believe this was related to carb loading. (I have never had that much carbs!)

However, my HDL continued to drop (slightly). This level was surprisingly lower than when I started! I would have expected it to increase or remain steady overall.

Points #4 and #5 are interesting because what I found earlier when researching the subject was that "in women, the volume of exercise (mileage) seems to be more important than the intensity of exercise for influencing HDL-C levels."

According to this study, increasing my mileage should have increased my HDL levels.

Interestingly, my triglycerides and LDL continued to increase during the couple of weeks after the race, even though my total cholesterol was somewhat stable, as mentioned in point #2.

General Conclusion

As mentioned in point #3, my total cholesterol went down again in February 2018 (with my "regular training") to about the same level as it was on race day.

This might be because exercise intensity decreases my total cholesterol just as much as, if not more than, duration, as mentioned above.

Most importantly, my triglycerides / LDL levels stayed consistently low during my "regular training," whereas they increased significantly about 4-5 weeks prior to the race.

The reason behind the lower triglycerides / LDL levels could be the relatively low-carb diet that I usually follow as part of my "regular training," as opposed to the high-carb diet that I had to follow as I increased my mileage.

References

(1) High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol in marathon runners during a 20-day road race.

Dressendorfer RH, Wade CE, Hornick C, Timmis GC.

JAMA. 1982 Mar 26;247(12):1715-7.

(2) A Review of the Impact of Exercise on Cholesterol Levels

Chantal A. Vella, Len Kravitz, Ph.D., and Jeffrey M. Janot

Brownell K.D., P.S. Bachorik & R.S. Ayerle. 1982. “Changes in plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels in men and women after a program of moderate exercise”. Circulation. 65(3):477-84.

Drygas W. et al. 2000. “Long term effects of different physical activity levels on coronary heart disease risk factors in middle-aged men”. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 21(4):235-41.

Duncan J.J., N.F. Gordon, & C.B. Scott. 1991. “Women walking for health and fitness. How much is enough?” Journal of the American Medical Association. 266(23):3295-9.

Dunn A.L. et al. 1999. “Comparison of lifestyle and structured interventions to increase physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness: a randomized trial”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 281(4):327-34.

Durstine J.L. & W.L. Haskell. 1994. “Effects of exercise training on plasma lipids and lipoproteins”. Exercise and Sports Science Reviews. 22:477-522.

Katzmarzyk P.T. et al. 2001. “Changes in blood lipids consequent to aerobic exercise training related to changes in body fatness and aerobic fitness”. Metabolism 50(7);841-8.

Kikkinos P.F. et al. 1995a. “Miles run per week and high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in healthy, middle-aged men. A dose-response relationship”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 155(4):415-20.

Kikkinos P.F. et al. 1995b. “Cardiorespiratory fitness and coronary heart disease risk factor association in women”. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 26(2):358-64.

Kikkinos P.F. & B. Fernhall. 1999. “Physical activity and high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels”. Sports Medicine. 28(5):307-14.

King A.C. et al. 1995. “Varying intensities and formats of physical activity on participation rates, fitness and lipoproteins in men and women aged 50-65 years”. American Heart Journal. 91(10)2596-04.

Lakka T.A. & J.T. Salonen. 1992. “Physical activity and serum lipids: a cross-sectional population study in eastern Finnish men”. American Journal of Epidemiology. 136(7):806-18.Seip R.L. et al. 1993. “Exercise training decreases plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein. Arteriosclerosis”. 13(9):1359-67.

Leclerc S. et al. 1985. “High density lipoprotein cholesterol, habitual physical activity and physical fitness”. Atherosclerosis. 57(1):43-51.

Lindheim S.R. et al. 1994. “The independent effects of exercise and estrogen on lipids and lipoproteins in postmenopausal women”. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 83(2):167-72.

Moll M.E. et al. 1979. “Cholesterol metabolism in non-obese women. Failure of physical conditioning to alter levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol”. Atherosclerosis. 34(2):159-66.

Neiman, D.C. 1998. The Exercise Health Connection. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Ready A.E. et al. 1996. “Influence of walking volume on health benefits in women post-menopause”. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise. 28(9):1097-105.

Santiago, M.C., A.S. Leon & R.C. Serfass. 1995. “Failure of 40 weeks of brisk walking to alter blood lipids in normolipidemic women”. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology. 20(4):417-28.

Spate-Douglass T. & R.E. Keyser. “Exercise intensity: its effect on the high-density lipoprotein profile”. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 80(6):691-5.

Stein R.A. et al. 1990. “Effects of different exercise training intensities on lipoprotein cholesterol fractions in healthy middle aged men”. American Heart Journal. 119:277-83.

Sunami Y. et al. 1999. “Effects of low-intensity aerobic training on the high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration in healthy elderly subjects”. Metabolism. 48(8):984-9.

Williams P.T. et al. 1982. “The effects of running mileage and duration on plasma lipoprotein levels”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 247(19):2674-9.

Williams P.T. 1996. “High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other risk factors for coronary heart disease in female runners”.334(20):1298-303.

Williams P.T. 1998. “Relationships of heart disease risk factors to exercise quantity and intensity”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 158(3):237-45.

Wood P.D. et al. 1983. “Increased exercise level and plasma lipoprotein concentrations: a one year randomized, controlled study in sedentary middle-aged men”. Metabolism. 32(1):31-9.

Wood P.D. et al. 1991. “The effects on plasma lipoproteins of a prudent weight-reducing diet, with or without exercise, in overweight men and women”. New England Journal of Medicine. 325(7):461-6.

Laila Zemrani

Twitter | Linkedin | http://lailazemrani.com